It was the 19th of January, my birthday. It was freezing. We were six persons in a small boat. The ocean water looked very dangerous. At one point, he youngest of us, a 14-year old boy, wanted to change his place in the boat. He slipped and fell down into the water. He couldn’t swim. Somehow we brought him back to the boat. After that happened, I was scared to death. One of my friend said ‘If I arrive in Greece I will kill one cow. The other one said: ‘If I arrive, I kill two cows’. But none of them killed any of the cows so far.

Azadi is laughing and with him the deep wrinkles that highlight his eyes like a corona the sun. Like many other refugees who get stranded on the Greek island Lesvos, Azadi escaped the war in Afghanistan. When he arrived, he was 19. That was one year ago. Because of the ethnic diversity in Afghanistan and his long journey to the fortress Europe, Azadi speaks many languages: Pashtu, Urdu, Farsi, Hindi, Greek, Turkish and English. I asked him about his long journey from Afghanistan to Greece. Because he escaped Afganistan with his mother and little brother several years ago to keep on living in Pakistan, this is where the story, that he is willing to share, starts.

If you cross the border from Pakistan to Iran, it means you risk your life. If the border patrol sees you, they have the permission to shoot you immediately. When the mafia took us in a truck from Pakistan to Teheran, the capital of Iran, we were 60 people in one truck. Sometimes they put 80 people inside. It took 24 hours. There was no food, no water. Nothing. You had to sit the whole time. You can’t stand. You are not allowed to ask for anything. No moving. No toilet. There were kids and women. A two year old child died in the truck. If the police would have caught us, they deport us back to Afghanistan. When we arrived near Teheran, the mafia dropped us. From there we had to walk to the border. The mafia said: ‘Be quick, run!’ First I couldn’t walk because I had to sit the whole time. I tried to, but I fell down. I was walking with other refugees for 40 hours. Some people walk one week. We had a small bottle of water for six people.

In Van, next to the Border, they put us in another truck. This time we were 70 to 80 people. Most of the people die here, on the way from Van, at the Turkish-Iranian border, to Istanbul, because it’s a very hard way. It takes more than 30 hours to arrive in Istanbul. In the big city the mafia releases you, if you can pay. I paid. But there were people who had not enough money. All the time, the mafia asks for money. During the traffic they say, the police is waiting outside, we have to pay them. And you have to because you are in the middle of nowhere, there is no place to go, no water, no food. And also on the borders you have to pay. To come from Pakistan to Greece, it cost me around 5000 US Dollar. But they are not only rich people who flee the country. In general, if people have too many problems, poor or rich, they start selling their lives. They sell whatever they can, they collect money from their families.

The refugees who did not have enough money in Istanbul were beaten up by the mafia who gave a telephone to call their families and to ask if they can send money over. They keep you as long as you can’t pay.

There is almost no tone in his voice left. It sounds as if he would get not enough oxygen. He looks to the ground. He says nothing. Sometimes for minutes. The struggle he fights is visible on his face. It is as if something would pull him back telling me all this. Then unexpectedly, he gathers some strength, continues telling about the last part of his journey. The part they travelled all by themselves. Almost.

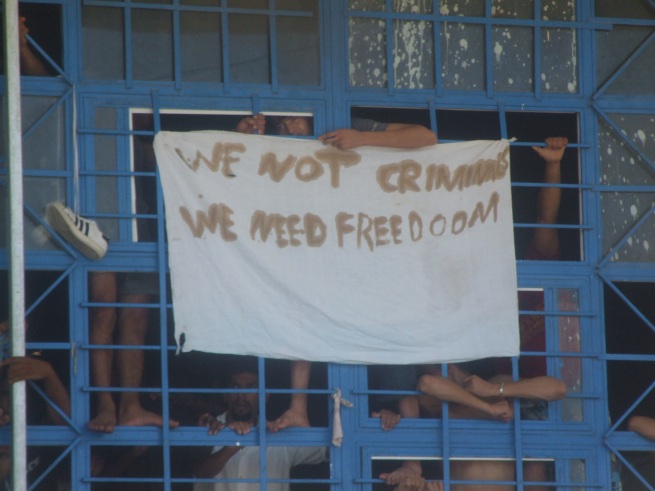

From Turkish mainland to Lesvos it took us five hours. At the western coast of Turkey the mafia told us ‘you have to go to the lights that you can see on the other side over there, this is Greece’. When we left with our boat, the Turkish navy saw us on the ocean. One of them called us, he asked: ‘Hey brother where do you go?’ We said ‘We go to Greece!’ and then ‘See you, bye bye’. They just let us go. The next police we saw was not Frontex. It was the Greek navy. They came and said: ‘Hey you, stupid,’ and they used other bad words, ‘where do you go?’ We said: ‘We need help, we want to go to Greece’. And then they said: ‘Go and die, we can not help you, go back to Turkey’. We said: ‘Okay’, and we turned the boat. So we went back and tried it again. The Greek navy came again and said: ‘Why are you here we told you to go back to Turkey’. ‘Yes’, we said, ‘but we want to go to Greece’. This time they took us, called the Pagani detention centre to ask if they have space for six afghan men. Then they took us to the hospital to x-ray and at two o’clock in the night they dropped us in Pagani. We knew about Pagani before. But we thought it’s a refugee camp with the facilities for refugees. We didn’t know it’s a prison. Pagani has to be closed because it is not a welcome centre. It’s a prison. There are no facilities for refugees. Even people who are here legally can’t do nothing.

Azadi was kept three weeks in the prison Pagani before he was released to an open camp for minors on the same island. The open camp is a former hospital for mental diseases in the middle of a forest, one hour by bus from Mytilini and one more hour by foot. In contrast to Pagani, the open camp in Aiassos is a paradise. An isolated paradise. The hundred young men who live here are free to leave the house whenever they want. They are on an island anyways. They can’t go nowhere. There are courses in Greek and sometimes in German, depending the volunteer’s countries of origin. Several volunteers, a Greek lawyer, two afghan cooks and a security officer are working there. Interpreters are lacking. There is a computer room. But most of the time the internet is not working. There is also a sports room. But right now it is stuffed with forty bunk beds that were ordered for new refugees who arrived recently in Lesvos. In very rare cases the refugees can work in Aiassos or nearby. Usually during the olive harvest. Most of them hang around in the house or the huge garden. They wait. For something. Azadi stayed one year in the open camp.

You get information about what you can do after prison from your friends. In Azadi you have a lot of free time, you talk. When I got the informations, I realized that this country is really bad for refugees. It is not a safe place for us. No place where you can think about a future. I have a friend from Afghanistan with very good education. He came to Greece to go to university. He got political asylum. But there is no way. He can’t pay his accommodation here. There is nobody who helps him, who shows him around even. They don’t care for you. You have to do everything by yourself. Even the organisations for refugees do not care really. They maybe tell you: Look you have to make it like this or like that but they don’t care in the end. Nobody here provides nothing for refugees. Even migrants who have the possibility to work, like him, who have political asylum, can’t find work. In the end even if you get the citizenship here, they can send you back.

Azadi has not been deported back. Maybe it was because he is able to communicate in many languages. Maybe because he is one of the few who got the political asylum. Maybe because he was lucky in unlucky times. He knows that being lucky is a condition that can vanish like a little boat in the big ocean sometimes does. Some of his friends have been hindered on their way. He knows their stories like his own.

In Greece when they try to deport you back to your country, the Greek police sends you to Alexandroupolis usually, close to the Turkish border. Then the Greek border patrol opens some fire in the night. At this time nobody notices that we are going to be sent back. They are scared of the media, of the Turkish army. With the fire the Turkish border patrol understands something happened. So they come and take us and sent us back with the plane to Afghanistan. But you have to pay your ticket. If you can’t pay, you have to go to a Turkish prison. I know people who had to stay in prison because of that for two years. Because they couldn’t pay their own deportation-ticket.

One year in Lesvos. Has he really been here the whole time? What happened during this one year? Did he try to go on, to reach another European country?

I decided to go to Athens and from there with the plane to Italy. I had faked papers. The police caught me on the airport and I had stay in prison for six days. But believe me, there is no other way than fake papers. You have to risk, even though we know that the police catches us many times and it is possible that they send us back to our country, there is no other chance. Now Greece has a new law that if you get caught at the airport with fake papers, you will stay for three months in prison. But there are certain days were it is easier for migrants to cross borders. Usually the tourist season is good or christmas.